OPINION: The Wikipedia Craze That Died

October 28, 2022

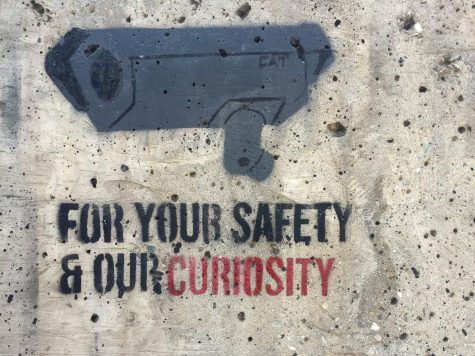

Around the mid-2010s, there was a craze for looking through I.P. addresses from Wikipedia to gain insight into corporations and governments. This trend had a fast burn, as it was brought up now for either news for partisan reasons or to laugh at Wikipedia vandalism. An I.P. address “is a unique address that identifies a device on the internet or a local network” (Kaspersky). I.P. addresses can be disguised using V.P.N.s, proxies, Tor, or privacy-themed operating systems like Tails, Whonix, and GrapheneOS. There are two types of I.P. addresses: the first one is I.P.v4 (129.23.0.0), which I found from the Strategic Defense Initiative (Star Wars Program), a U.S. government missile defense system. The second one is I.P.v6 (2001:1458:202:42::101:6cdd), which I found from the European Organization for Nuclear Research (C.E.R.N.). There are people that complain about how I.P. addresses can be used by hackers. However, hackers can hack anything with an internet connection, and it is relatively easy for them to gather I.P. addresses from Wikipedia. Of course, the hard part is getting a specific one. I.P. addresses themselves are public information, and each website you visit sees your I.P. address.

The trend was technologically simple and did not require much skill to mine I.P. addresses from Wikipedia. All people needed to know was how to navigate to user contributions and view history on Wikipedia as well as been able to access a site that searched up I.P. addresses. However, this process was slow and required a lot of time. Eventually, some individuals automated this process with code, which lead to faster results and even made some people slightly famous. The trend began with a man named Virgil Griffith, who at one time had a website called WikiScanner, which was released in August of 2007 and shutdown the same year. The site allowed users to search tons of I.P. addresses by name. WikiScanner was so successful that it eventually led to its own downfall because Griffith was unable to keep up with paying for the site; as a college student, he could not afford several thousands of dollars per month to run the site. Wikiscanner was the reason why there were tons of news outlets publishing articles that showed the I.P. addresses of the CIA and the FBI. The trend was reviled by Twitter Bots that tweeted each time certain I.P. addresses were edited on Wikipedia. This was pioneered by YouTuber Tom Scott, who created Parliament Edits in July of 2014; it would foster copycats, most notably CongressEdits, that same month. Eventually, with no room to go forward after several years, the trend died off as people got bored of the I.P. address and Wikipedia crazes, and news sites, for the most part, stopped reporting on the matter. People still collect I.P. addresses today, usually either just people on the internet or news journalists. However, the number of people still continuing the collection today cannot beat the large group of people that make the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. You can get more information from them, but the government agency might make you pay for it.