Rape Culture on Campus: @RMCSilences Attempt to Hold Accountability and Make Change

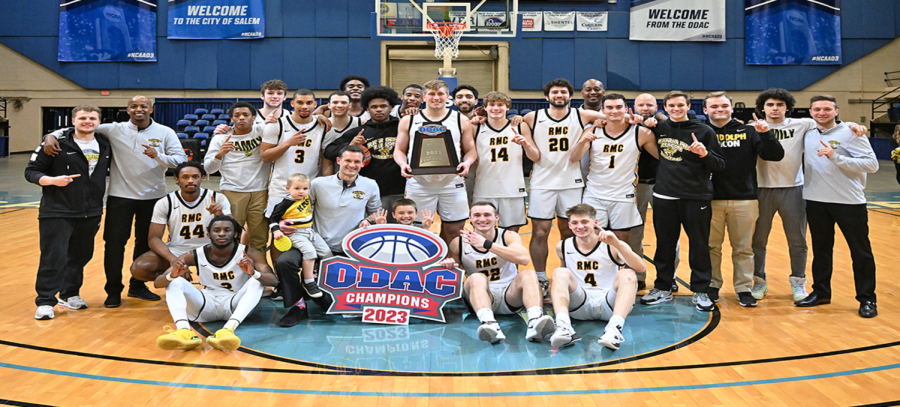

Jonah Prater (left) and Wren Wilson (right) at R-MC Silences protest. Photo via @rmcsilences on Instagram.

February 16, 2022

Foreword:

This article contains a discussion of subjects that may be distressing to sensitive readers, including extensive coverage of sexual assault and a brief mention of suicide.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault or suicidal ideation, there are many on- and off-campus resources available to you, and none of the following should be construed as discouragement from taking advantage of those or any other on-campus resources:

Campus Safety: 804-752-4710

Counseling Center: 804-752-7270 (after hours: dial Campus Safety and ask for the Director of Counseling Services)

Student Health Center: 804-752-3776

Hanover Safe Place 24-hour hotline: 804-752-2702

Title IX Office: 804-752-3295

A full list of resources can be found at rmc.edu/offices/title-ix/resources.

“@RMCSilences” made its last Instagram post in November 2021: “New petition just dropped!”

The campaign had made no small impression on campus during the fall semester. They introduced themselves in September by way of a series of impassioned and controversial flyers whose allegations that Randolph-Macon “PROTECTS RAPISTS and THREATENS VICTIMS” quickly prompted an email from the Office of the President to the student body. In response, the organizers began circulating a second flyer that called this email “blatant lies” and asserted that the College had violated Title IX, a federal law that aims to prevent discrimination on the basis of sex in educational institutions.

The organizers staged two modestly attended protests on Henry Street in late October and early November, partnered with the philosophy club to host a dialogue on campus sexual assault, and even claimed to have prompted a Department of Education investigation into the College’s conduct. They were audacious, idealistic, and brash: all the more strange, then, that they appeared to simply peter out in November. The Instagram page now lies deserted; the “new petition just dropped” accumulated only 43 signatures.

@RMCSilences naturally leaves several pressing questions in the wake of its dizzyingly rapid rise and fall. Where did it come from, and what happened to it? Did its unforeseen burst of activity in the fall amount to any tangible changes? Perhaps most importantly: what comes next for those who supported the movement?

The two students primarily responsible for promulgating @RMCSilences are Jonah Prater ’23 and Wren Wilson ’23. They sat down with YJ News for one on-the-record interview and agreed to share some of their communications and materials.

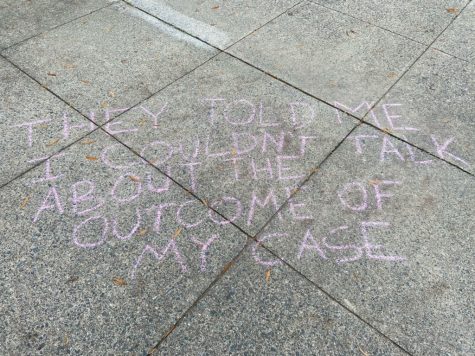

Their ire was galvanized by a friend’s Title IX hearing which they had found frustrating in several respects. Notably, they were upset that the complainant was told not to discuss the outcome of the case. As Wilson explains, “[The complainant] told me, ‘Yeah, I won’, and then a few days later, she said, ‘They’re telling me I can’t talk about that.’ So that was kind of where the case itself ended and the after-effect bullshit started.”

“When I started writing those [flyers],” Wilson explains, “it was intended to be inflammatory in a sense of a lot of people respond to that and also that’s what scares the school [….] Obviously, looking back, I was pissed and [that was] possibly not one hundred percent the most effective way to pressure them.” Since that email, the school has not addressed @RMCSilences publicly and has been, in the organizers’ view, illiberal in their direct communications. “They haven’t corresponded with me at all,” says Wilson. “They’ve not once reached out to me to talk, and I’ve reached out to them multiple times about the issues that I have […] so they’re very much not interested in having a dialogue, they’re more interested in shutting down what I’m doing.”

Is it true, then, that any of Randolph-Macon’s conduct may be legally actionable? The short answer is ‘probably not’ – but the conduct in question should not go unscrutinized.

The allegations of illegal conduct come from the second flyer @RMCSilences circulated in mid-September, which read:

“RANDOLPH MACON [sic] HAS BROKEN AT LEAST TWO FEDERAL TITLE IX LAWS IN THE LAST TWO MONTHS [….]

“It is illegal to, [sic]

“1. Tell the victim that they cannot discuss the outcome of their Title IX hearing, and

“2. Retaliate against a victim when they [the victim] exercise their right to discuss these things with threats of punishment.”

Wilson says these accusations arose out of “the retaliation subsection of Title IX law.” Title IX of the Education Amendments does not actually have a retaliation subsection. Rather, this appears to be a reference to 34 CFR §106.71, a Trump-era regulation which disallows schools and individuals to “intimidate, threaten, coerce, or discriminate against any individual for the purpose of interfering with any right or privilege secured by Title IX or this part, or because the individual has made a report or complaint, testified, assisted, or participated or refused to participate in any manner in an investigation, proceeding, or hearing.”

In short, @RMCSilences argues that the enforcement of any confidentiality policy is inherently an act of retaliation. This is a fraught territory: the assertion that §106.71 disallows R-MC to require confidentiality of complainants and respondents relies on the premise that the potential code of conduct charge thus arising is a direct reaction to the complainant’s having participated in the grievance rather than their actions after its adjudication.

Wilson justifies this position by pointing out, correctly, that the Department of Education has deemed it against policy for schools to require that students sign non-disclosure agreements to learn the outcome of their Title IX hearing. This is, however, a false equivocation of NDAs with the confidentiality requirement in R-MC’s student code of conduct. The code of conduct is only enforceable during one’s time as a student (hence alumnus’ ability to speak freely to YJ News about their cases) and such enforcement is performed only by the school and not the legal system; NDAs are enforceable by the civil courts for the lifetime of the signee or an otherwise specified period of time, and a violation thereof could result in legal troubles for the signee. In an email to Wilson, Title IX Coordinator Laura Soulsby confirmed that NDAs are not a part of the Title IX process at R-MC, and none of the complainants with whom YJ News has had contact have claimed that they signed an NDA.

Curiously, §106.71 also includes a confidentiality clause which opens up some gray area: “The recipient must keep confidential the identity of any individual who has made a report or complaint of sex discrimination, including any individual who has made a report or filed a formal complaint of sexual harassment, any complainant, any individual who has been reported to be the perpetrator of sex discrimination, any respondent, and any witness.” (“Recipient” in this context means the recipient of a complaint; i.e., the educational institution). Then, no employee of a school may disclose the identity of any participants in a hearing. But the phrase “must keep confidential” could be interpreted as implying that schools also have a responsibility and authority to prevent said participants from disclosing each other’s identities; this appears to be the reading favored by Randolph-Macon. Dr. Soulsby explains: “In line with the recent update to Title IX federal law,” that is, the Trump administration’s 2020 update known as the ‘Final Rule,’ of which §106.71 is a part, “our Sexual and Relationship Conduct policy requires that all members of our community maintain confidentiality, to the extent possible, of all Title IX-related reports and matters, including hearings, and our policy also prohibits retaliation.” That said, the College cannot claim its confidentiality policy was foisted upon it unwillingly; a version of that policy has been in place since at least 2008.

@RMCSilences and the College administration manage to come to two mutually exclusive conclusions regarding the same piece of text. Neither interpretation has yet been endorsed by an adjudicating body, and the regulation itself may soon change, as the Biden administration is currently in the process of reviewing and revising the Final Rule. In the meantime, Wilson did file a complaint to the Department of Education which could result in an investigation of the matter.

And while a reasonable observer could make a principled argument against having a confidentiality policy, a more salient complaint than one of its existence may be of its enforcement. Speaking with alumni, YJ News found several historical incidents of R-MC’s failing to protect complainants from retaliation and to enforce its confidentiality policy.

Ivana Moore ‘19 writes, “[My assaulter] was a member of the football team. I was bullied and harassed by people I went to the party with that night and by members of the football team.

“[R-MC] just did those no-contact orders and threatened him and the football players I named that they would get a conduct hearing. But the harassment was so bad and they did not do anything that I [sic] just stopped reporting stuff.”

Jessica Ramirez ‘19’s story is troublingly similar in this regard. “I had to get a [no-contact order] done because [my assaulter’s] girlfriend turned my sorority against me, and they were kind of pushing him in my face,” she recounts. “I used to work at Greenberry’s, and they would bring him to Greenberry’s to kind of be like, ‘oh, what’s wrong?’ I got a lot of hatred from the football team because he was a football player. People were saying how I was ‘ruining his future’… there was a lot of slander going on.”

Again, there are legitimate pros and cons to having a confidentiality policy, but to be expected to protect a respondent’s confidentiality only for that respondent to face no consequences for failing to hold up their end leaves complainants feeling they got the worst possible outcome on both ends. Granted, R-MC cannot disclose details on any case or, therefore, provide an explanation as to why any particular action did not result in a conduct violation. But there is an identifiable pattern at play here. @RMCSilences hindered themselves by presenting an abstract and weak legal argument rather than focusing on the practical application of the policy.

Of course, @RMCSilences’ complaints go far beyond the allegations of illegal conduct, and each merits further examination. The following list is inexhaustive, as Wilson and Prater brought up a myriad of concerns that evolved throughout their advocacy. It details the points which were brought up most frequently and which were repeated by other sources.

Sexual history

The Sexual and Relationship Conduct Policy is quite clear that any questions or evidence about a complainant’s sexual history are inadmissible in a hearing except in a few specific and rare circumstances, and the procedural protections for those accused of sexual misconduct outline their right “not to have past sexual history discussed during the hearing unless it is highly relevant, and it would not be manifestly unfair to consider such information.”

Wilson argues for the respondent’s rights to be weakened in this regard. “The problem with that that I find is that actually, it restricts relevant information because the respondent in [an] incident […] has a history of being accused of sexual assault in the past, and that wasn’t allowed to be brought up even though it’s quite relevant, in my opinion, and so I don’t know if that’s, like, how it’s supposed to operate federally under Title IX, if you’re not supposed to be able to bring up things of that caliber, or like any sexual history, because also: It wasn’t like, oh, he’s slutty, it’s like, he has committed crimes in the past of this nature and so it is more likely that he’s guilty this time. He’d been accused multiple times, like, something’s going on there.”

To the question of Title IX law: again, there is no statutory language about the hearing process. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) offers guidance on complainant sexual history, which is identical to the stipulation in Randolph-Macon’s Sexual and Relationship Conduct Policy. It does not address the potential relevance of respondent sexual history. In criminal court, prosecutors cannot use prior convictions as evidence that a defendant is guilty of a given crime but can in some cases use those convictions to impeach the defendant’s credibility; even so, in the case Wilson describes, the respondent’s prior accusations were never investigated would almost certainly preclude admissibility. However, the Title IX grievance process is not a criminal proceeding, so the relevance thereof is limited.

As things currently stand per the Final Rule and College policy, complainant sexual history can only be considered if it may establish the possibility that somebody other than the respondent committed the assault or that a “reasonable person” may have presumed consent in the context of the complainant and respondent’s historical consensual sexual activity with one another. The latter caveat raises some obvious concerns.

In the best of faith, it could be interpreted as an acknowledgment that some people do engage in unconventional but healthy and enjoyable sexual behavior, in which participants consciously redraw the generally acknowledged boundaries of affirmative consent. That is normal for two people to develop means of communication with one another which would be meaningless or confusing to an outside party because the meaning is derived from their shared history. In a less-than-ideal circumstance with a bad-faith or narrow-minded adjudicator, of course, one can imagine this nuance being perverted into a version of victim-blaming or an incomprehensive analysis of the respondent’s defense.

To be clear, complainants should never be asked about their sexual history as a means of establishing that said history would make them more or less likely to have given consent to the encounter at hand, nor should questioners ever insinuate that a victim did not struggle enough or equate a lack of explicit nonconsent with “implicit” consent. These restrictions are acknowledged in the College’s sexual assault procedural training.

Timely Warnings

In compliance with the Clery Act, institutions of higher education are supposed to issue “timely warnings” to the campus community about reported crimes that are “considered by the institution to represent a threat to students and employees,” (34 CFR § 668.46 (e) (2)). An example of such a warning would be the email students received from campus safety about vehicle break-ins on January 8th. Timely warnings for sexual assault are now quite rare.

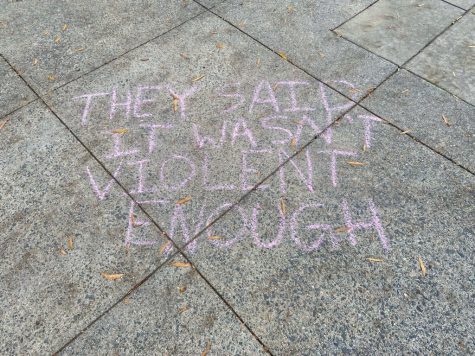

Ramirez asked why her reported assault did not prompt a timely warning. “They said that my assault wasn’t ‘aggressive enough.’ So they didn’t send an alert for me, and I thought it was weird that it was all sort of hush-hush,” she said.

Wilson believes this dismissal was intentional and indicative of a conspiracy of silence. “I think [the College] started phasing out [the text alerts] by saying that to people, and then once everyone had graduated who knew that used to happen, they didn’t have to talk about it anymore,” Wilson said. “Essentially my opinion is that an assaulter is an ongoing threat and the campus is making no effort to warn the community. So they have fairly malicious intent in keeping those things under wraps, in my opinion.”

The decision of whether and in what manner a timely warning should be issued falls on the Behavioral Assessment/Intervention Team (BAIT), and their process for doing so is opaque. Dr. Soulsby offers only that “Their decision [whether or not to issue a timely warning] is subject to a series of considerations for the safety of our entire College community.”

There is little existing research on timely warnings and their efficacy but some evidence that the warnings can do more harm than good in some cases (although whether these concerns are considered by the BAIT is, again, unclear). These concerns include that timely warnings could contribute to a victim-blaming culture by implying an onus on women, in particular, to behave more carefully, that they could compromise the identities of those involved and potentially subject complainants and witnesses to retaliation, that they could discourage others from reporting their assaults, and that they could re-traumatize the victim and any readers who had also experienced sexual assault.

When YJ News asked students about sexual violence on campus in 2019, two students mentioned the timely warnings and expressed similar concerns to those aforementioned.

“The school and the timely notices are ineffective and useless,” said one junior.

“The one time I recall receiving an email about an assault on campus, it left me with a very alienating feeling,” recalled a senior named Anna. “If I was the one referred to in that email, I would have been mortified that it was spread around campus, even without my name being mentioned. It made me think that I wouldn’t want to report it on campus.”

Wilson believes the benefits of a timely warning in a given situation outweigh those drawbacks. “Essentially the purpose is to, first of all, let people know that they take [sexual assault] seriously,” they said. “So if potential rapists see this pop up on their phone, they’re like, ‘oh. They take this stuff seriously; I would rather not be the person on the other end of that.’ Additionally, it lets other victims know if you ever have a problem, [the College] will do everything to keep you and other people safe. They are warning folks that, you know, maybe for the next few weeks don’t go out alone at night.”

As a means of increasing the likelihood that a warning goes out for sexual assault cases, Wilson had proposed that “student boards should be involved [in the decision to issue a warning] because we’re the community it’s affecting.” This is a reasonable principle, but likely not possible because of the sensitive information involved in timely warning decisions.

Sanctions

“One of the parts of restructuring the Title IX process was the fact that we want crimes to be less vaguely defined as well as the punishment for those crimes,” Prater said. “If you commit rape, you’re found guilty of sexual harassment, which they could give you any range of punishments for. So if somebody is found guilty of rape, specifically as definition, rape, then there should be a list of punishments that should be published for people to see, so that it’s not like, ‘Oh, this person was found guilty of rape,’ they’re not going to be able to be like, ‘Oh, rape, community service.’”

“To be clear,” writes Dr. Soulsby, “the Title IX office is a campus grievance process. The criminal process is entirely separate.”

Because Title IX offices exist to facilitate schools’ compliance with Title IX by ensuring a safe and equal learning environment for women, the office’s duty to adjudicate sexual harassment complaints is based solely on the nature of sexual harassment being a limiting force on women’s access to education, not on its being a criminal act. The Final Rule allows but does not require schools to punish respondents who are found to be responsible for harassment, and generally what sanctions are metered out are so done for the benefit of the victim rather than as detriment to the assailant. Usually, the goal is creating enough separation between the complainant and respondent to ensure the complainant’s ability to move freely about campus without fear. This approach assumes that an assailant is only a danger to the victim they have already assaulted rather than, as Wilson views it, “an ongoing threat” to the entire campus community.

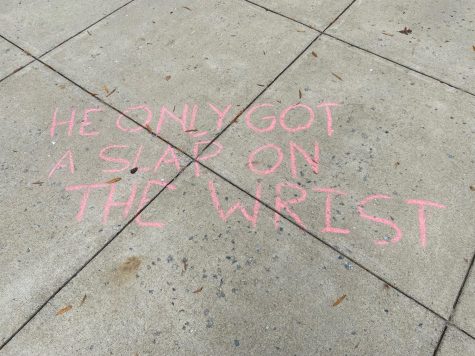

Moore describes her assailant as having been one such ongoing threat. Despite having been temporarily suspended from campus after being found responsible for assaulting her, “[t]he guy went on to rape more women, had more [Title IX] trials, had a gun on campus and was kicked out of school only after he was failing his classes and lost his scholarship.”

Besides the simple matter of preventing future assaults, some students may turn to the Title IX office as a means of achieving justice alternative to the criminal justice system, given the latter’s reputation for hostility towards sexual assault victims. When the school does not treat those respondents with the same severity as the criminal courts would a guilty defendant, their victims feel understandably slighted. “One of my greatest regrets is that I wish I would have gone to the police,” says Ramirez, “because I feel like [my assailant] barely got punishment for what he did. His ten minutes of fun, that’s done, but for me, that’s a lifetime of pain.”

Prater’s proposal that punitive measures be standardized would protect the school from accusations of protecting respondents with arbitrarily lenient sanctions and give victims a clear idea of what they can expect out of the process. But it would come with several issues of its own. It would make the Title IX process significantly more similar to the criminal justice system than it is presently and thus subject to some of its same drawbacks. Most notably, it would necessitate a higher evidentiary standard for determining responsibility than the ‘preponderance of evidence’/50% standard currently in place, wherein the complainant must be able to threshold a greater than 50% chance that their claim is true as evaluated by the adjudicator (this is as opposed to “beyond a reasonable doubt”, the evidentiary standard used in criminal procedures), thus increasing the burden on the complainant; and it assumes a one-size-fits-all meaning of justice for each victim, potentially alienating victims.

It is not the case that R-MC can only treat respondents with either excessive leniency or heuristic punishment. We could move forward with a victim-centered approach to these cases based on the principles of restorative justice: emphasizing righting the wrongs done to the victim and community rather than on blame and punishment. Restorative justice programs generally involve facilitated face-to-face meetings of the stakeholders wherein the perpetrator accepts responsibility for the harm caused to the victim and participants collaboratively make an action plan, which may or may not include the types of sanctions that can come out of the hearing process, such as no-contact agreements. Both the victim and perpetrator have to consent to the restorative approach; it would not eliminate the need for Title IX hearings. But it would give complainants another option with which to achieve justice, one which does not require that they yield any autonomy thereover.

Victim Support

Being as they were focused on the hearing process and punishments, Wilson and Prater did not often bring up victim support during interviews, except to propose that the College should host a victim peer support group. But Jessica Ramirez, who suffers from PTSD stemming from her on-campus sexual assault, feels that victim support is a crucial area in which the College could be doing better. “I feel like I was interrogated, interrogated again with people in front of me, and then I was just released,” Ramirez said. “No follow-up, like, ‘hey, how are you doing?’ If I wasn’t mentally stable, I could’ve killed myself – nobody followed up with me, nobody would have known how I was doing.”

The Title IX office does have a page on rmc.edu dedicated to resources that victims of sexual assault can utilize, and students are always encouraged to make use of R-MC’s counseling services. But Ramirez feels that there should be a proactive support system for those going through the Title IX process in addition to those resources. “Maybe even have someone dedicated to the role of talking to people going through sexual assault. It would be nice to have someone who’s in that, and to kind of have an ally,” she said.

In addition to emotional support, students who have experienced sexual assault may need academic support. “My grades, they dipped a lot,” Ramirez said. “I almost wish they would’ve told me that I could’ve taken an incomplete and that I could finish [my classes] later or over break because I couldn’t get into the graduate program I wanted to get into because my GPA was not high enough. So I just feel like they could have aided the victim more; told them about these resources, these are options you can have. If you’re struggling academically, these are some paths you can take.”

Victim support goes to the very heart of why Title IX offices exist: to minimize the effect of sexual discrimination, including sexual harassment, on students. Ramirez’s case was one of an unequivocal failure on the College’s part which it should make every effort not to repeat. Such failures could be averted by doing as she suggests: creating a position within the office specifically for supporting individuals who have experienced sexual assault during, after, or absent a hearing process. That person could reach out periodically to victims, lend a confidential ear, connect them to more comprehensive mental health support if need be, advocate for whatever academic accommodations they may need, and ensure that all remedial actions, such as no-contact orders, are enforced.

@RMCSilences is unlikely to stage a revival this spring. Wilson, who had been its main driver, has since left R-MC and is now employing their passion and their desire to organize as the chair of Virginia’s Young Communist League.

The movement undermined itself by throwing out accusations of illegal conduct which it was ultimately unable to back up and which led the College to conclude that ignoring them would serve it better than engaging with them. Their assertion that the same reckless disregard for the complexity of human relationships which contributes to rape culture in the first place should be employed in dismantling it ultimately turned people off. But they had built up a minor following early on because they identified an issue which has long since been controversial on campus. YJ News’ previous coverage of sexual assault on campus revealed deeply divided perceptions of the Title IX process. Theirs may have been the loudest, but it was not the first and certainly won’t be the last student effort to change how sexual assault is handled on campus. And though it did not create any immediate policy change, one can reasonably hope that the conversation it started will have some impact down the road.

In the meantime, the Title IX process is likely to change again very soon: the Biden administration is currently revising the Trump-era Final Rule that was responsible for some of the policies with which @RMCSilences took issue.

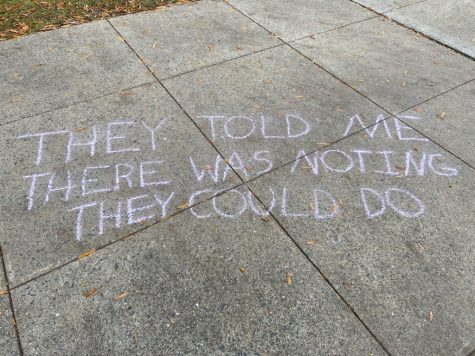

*All sidewalk photos were taken by Veronica Fernandez on October 30, 2021.