The Failed Legacy of Being “Tough on Crime”

March 9, 2022

Notice: This article presents a controversial idea that is not affiliated with the Yellow Jacket Newspaper. We encourage open dialogue and welcome respectful responses from the R-MC community. If this is a topic you feel strongly on, please consider writing your own piece to be reviewed and possibly featured in our next release by emailing it to [email protected]. Thank you!

“I watched a man cut his penis off,” said the former inmate testifying on the Virginia Senate floor.

The topic of discussion was Senate Bill 108, a piece of legislation that would severely limit the use of solitary confinement in the Virginia criminal justice system. Several former inmates had come to the Senate to argue in favor of the bill, recounting many of the horrors and trauma they had experienced during their time in Virginia prisons. Criminal justice reform has become a contentious topic in recent years of American politics. Despite making up 5% of the world population, the U.S. shockingly houses 20% of the world’s prison population. Institutional prejudice, the death penalty, solitary confinement, wrongful imprisonment, and the prosecution of victimless crimes are just a few of the major problems that plague the justice system. Unfortunately, any attempt at reforming the justice system meets stiff opposition in the form of a brick wall painted with the words “Tough on Crime.” These three words have become the doctrine of those who oppose justice reform. They are often accompanied by the phrase “Weak on Crime,” which functions as a scarlet letter to be branded upon any politician who attempts to seriously rethink the justice system. The path forward is clear: to create a system that truly embodies the American values of liberty and justice, we desperately need to transcend the simplistic contradiction of toughness and weakness as it relates to criminal justice.

Let’s start by identifying where exactly this type of thinking began. In June of 1971, Richard Nixon formally declared a “war on drugs.” The declaration was a response to the rising drug culture of the late 1960s which saw the widespread public use of marijuana and psychedelics. Nixon’s top aide, John Ehrlichman, revealed that the hidden justification behind this declaration was an attempt to “associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then (criminalize) both heavily.” Ehrlichman continued in arguing that this association gave Nixon the power to “disrupt those communities… arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.” The Nixon presidency ultimately succeeded in its goal of disrupting mass amounts of the American population. During the period from 1974 to 2014, the incarcerated population increased by 600%, growing from approximately 200,000 people to 1.5 million.

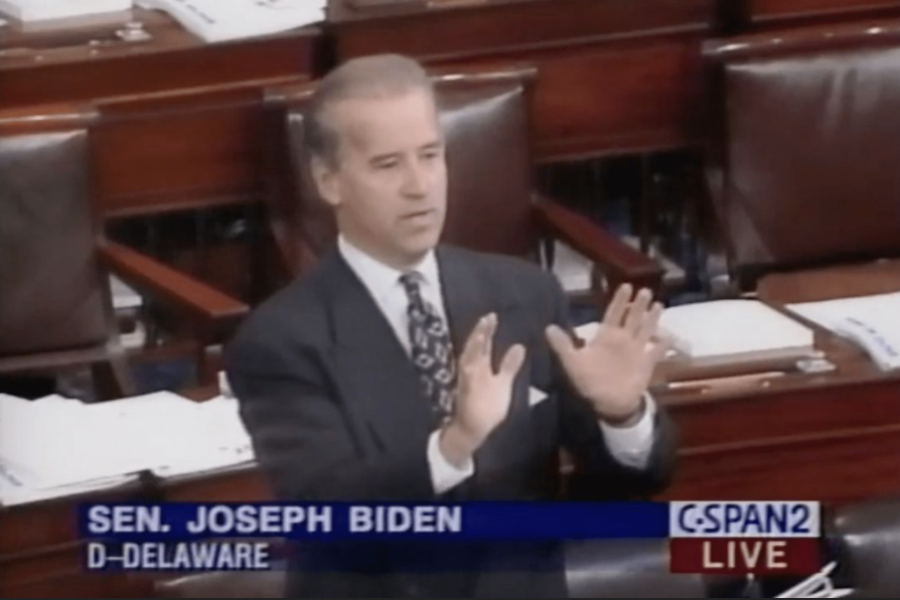

Later President Ronald Reagan succeeded in not only intensifying the war on drugs, but also making it a popular idea among the American people. Reagan fundamentally changed the political landscape of America and Democrats were forced to play in the environment that he created. Elections were being lost on the basis of accusations like being “weak on crime”. Republicans were dominating the Democrats, controlling the White House for three consecutive terms, and winning by margins so large they would be unimaginable by contemporary standards. The Democrats had to evolve or die, so in the late 1980s, they launched the “New Democrat” movement, promising to be tough on criminals and drugs. One of these New Democrats was then-Senator Joe Biden. Speaking in support of his 1994 crime bill, Biden said that “you take back the streets with more cops, more prisons, more physical protection for the people.” He flaunted his record of supporting tough-on-crime type legislation and said that “we cannot make rehabilitation a condition for release”. Biden also spoke enigmatically about a group of people growing up without parents, who would later become “predators” to society. The terms “predator” or “super predator” are now understood to be racist dog-whistling by many contemporary democrats.

Ultimately, the result of all these pieces of legislation has been nothing short of a complete failure at reducing crime, ending drug abuse, and creating a peaceful society. Instead, these tough-on-crime efforts have destroyed lower-income neighborhoods and have failed to decrease drug overdoses. These policies haven’t had their desired effect on drug reduction as they fundamentally alienate addicts and prevent them from seeking help. There is almost no credible evidence that increasing punishments for criminals deter people from committing crimes. Furthermore, punishments like the death penalty and mandatory minimum sentencing laws can unintentionally punish innocent people wrongfully accused of a crime. The problem runs deep into the underlying premise fueling these types of laws, that being the Hobbesian notion that the state can dictate the morality of society. Making heroin illegal doesn’t prevent anyone from doing it if the moral sentiment of the individual is positively disposed to drug use. The criminalization of narcotics also incentivizes illicit drug manufacturers to create more potent drugs with a higher dose to size ratio. An example of this principle would be fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is fifty times more potent than heroin. Drug smugglers can more easily hide fentanyl from law enforcement, as one dose of the drug is one-fiftieth the size of the same dose of heroin. The end result is the proliferation of a more lethal drug with a higher overdose potential.

To transcend this type of thinking, we need to recognize that not every issue requires a war to win. The problem is not the recognition of toughness as a virtue, the problem is how our society defines being tough. Anger, hatred, and vengeance are the emotions that drive tough-on-crime policies. Weakness is the inability to overcome these vindictive emotions. Being tough means being able to regulate these impulsive emotions and embrace rationality as a means of justifying public policy. Being tough means voting for the right policies, regardless of the accusations that may be hurled your way. In the case of the previously mentioned Senate Bill 108, weakness beat over strength. The bill was gutted by the house of delegates before it could be signed into law.